The guardians of the currency turn 200

Things can go very badly if a central bank is not independent of government authority. The history of the Norwegian monetary system has many examples of very unfortunate political interference.

11.11.2014 - Text: Sigrid Folkestad Photo: Helge Skodvin

"At present, Norges Bank has considerable independence, but we have seen that things can go very badly if a central bank is not allowed to operate independently," says Jan Tore Klovland, a professor in the Department of Economics at the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH).

The central bank will celebrate in 2016

In 2016, Norges Bank will turn 200. To commemorate this occasion, a non-fiction book shall be published by and for economists.

Klovland is one of three researchers who are writing the work on monetary history and Norges Bank. Together with researcher Lars Fredrik Øksendal and director Øyvind Eitrheim, both employed at Norges Bank, he is working on a manuscript that shall be published by a major international publisher.

In the chronological 200-year time line that they present, financial crises will attract attention. When the financial stability becomes shaky, the economic policy and the central bank's ability to manoeuvre become clearer.

Crucial moment

"Because these are 'triggering moments'. Crises trigger measures and drive the further development of the central bank, and the discussion about the division of labour between the central bank and the authorities is fundamental, especially in times of crisis," says Lars Fredrik Øksendal.

Klovland thinks that an extreme example of political intervention occurred during the First World War, when the central bank was more or less forced to cash out for the government. The bank injected large amounts of money into the economy, which resulted in an extremely bloated economy, which finally burst.

"Two major mistakes were made. Far too much money was injected into the economy from the time of the First World War until 1920. After that Central Bank Governor Nicolai Rygg introduced a deflationary policy.

Double fault

This is a course of action that Klovland has witnessed many times in monetary history. He compares it to mistakes that are made by a tennis player.

"The tennis player can commit a double fault. He has two serves. The first serve is much too weak and hits the net. That is the expansive phase with the injection of money. The second serve is too hard. That was Rygg's deflationary policy. The same thing happened in Norway during the 1980s, but on a smaller scale. First they were too lax; then they may have tightened things up to much.

Much space is devoted to the pari policy and the banking crisis of the 1920s. The financial crises of 1848 and 1857 are also very well covered.

"It can explain important conditions at the time and show how the bank acted," says Klovland.

"Crises serve as a test for the central bank and the financial system, and a crisis will often result in change. Therefore, crises are a very important point of departure when we study the central bank's development," notes Øksendal.

Crises and recoveries over 200 years

As the upcoming book's title, "The Monetary History of Norway 1816-2016", indicates, the authors cover much more ground than a mere description of the developments at Norges Bank.

"There is nothing else to compare it with except Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz's magnum opus from 1963, "A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960" (1963). They begin the book with the following sentence:

"This book is about the stock of money in the United States".

"Essentially," says Øksendal, "that is what we are doing as well. We study the money supply and the institutions and factors that contribute to monetary development over a period of time.

Øksendal has the main responsibility for the period 1850-1914, a period of conflict where Norges Bank went from being a bank of issue, which primarily had responsibility for ensuring that the bank notes would be convertible to precious metal, to becoming a central bank, which ensures that the whole monetary system is functioning.

Klovland pays particular attention to the period between the two wars. The director in Norges Bank, Øyvind Eitrheim, focuses on the first historical epoch prior to 1850.

First savings bank in 1822

After Norges Bank was founded in 1816, the first years were characterised by the development of a new nation, a new national bank and a new monetary unit.

In 1822, the country's first savings bank was founded: Christiania Sparebank. After the capital got a savings bank, small banks popped up in almost all Norwegian municipalities, and throughout the whole of the 19th century the vast majority of borrowers were in the general public.

"In the 19th century, the savings banks were very heterogeneous. In the cities, the ideal of getting the lower classes to save was abandoned relatively quickly in favour of general banking activity. In the rural areas, they could be more or less a circle of savers who met every other Saturday in order to accept deposits or give loans," says Øksendal.

Commercial banks in Oslo and Bergen

The first commercial bank did not come until Christiania Bank og Kredittkasse was established in 1848. A few years later, Bergens Privatbank was founded in 1855.

The banks did not become major borrowers from Norges Bank until the period from around 1899 until the First World War. By then, the savings banks were well-established, and the rural areas conducted their normal banking transactions.

"Out in the periphery, the savings banks were very locally based. Some of them originated in old municipal stores of grain, which were gradually wound up. This trend picked up speed especially after the 1840s. Prior to that, many municipalities had bought up stores of grain out of fear of not having enough in reserve if the country lost access to grain as Ibsen described in "Terje Vigen", when the country was exposed to a grain blockade," says Klovland.

Not yet the banks' bank

The responsibility for the savings banks was delegated to the Ministry of Finance. Norges Bank was supposed to ensure that the bank notes were redeemable in precious metal, not that the savings banks had enough liquidity.

Around 1890, Norges Bank was given a broader responsibility. Nine years later, Kristiania was severely shaken by a financial crisis. With the so-called Kristiania crash, Norges Bank's responsibility was tested in practice.

"That was the first time Norges Bank gave liquidity support to banks in trouble. However, the goal was not to save banks, but to avoid a serious collapse of the monetary system.

After many years of immigration, expansive house building and generous loans, the bubble burst in the capital. Many businesses went bankrupt, and unemployment increased rapidly. Norges Bank had to intervene to provide liquidity to crisis-ridden banks.

"That was the first time Norges Bank provided massive loans to banks in crisis. It is possible that the rescue packages to the banks in the capital can be seen in context with the move of the head office of Norges Bank from Trondheim to Kristiania two years earlier," suggests Øksendal.

From Trondheim to Kristiania

The researchers think that Norges Bank's initial location in the capital of Trøndelag was due more to political horse trading and regional policy initiatives than to high quality assessments as we would like to believe.

The work in Norges Bank was largely characterised by practical assessments and systems related to banknote handling.

"The picture we have of a central bank that is a strong knowledge-based organisation with many economists began to slowly take shape in the 1960s," says Øksendal.

"The Ministry of Finance had very strong control over Norges Bank in the 1950s and 60s. At that time, a number of economists thought that they could close down the central bank and let it become a tabling office in the Ministry. After all, they were economic planners, and they thought that the real economy was the most important, not the monetary system," says Klovland.

"This was a time when the thinking was in terms of access to real resources such as bricks, nails, and manpower and when you plan with real resources, money is merely bookkeeping," adds Øksendal.

"The economists in the Ministry of Finance were supposed to decide upon and set the guidelines; it was not up to Norges Bank," notes Klovland.

"Was that a power struggle?"

"No, because the Ministry had the power. It went hand-in-hand with the concept of the centrally controlled planned economy.

Risky policy

The central bank did not gain control over the key interest rate until 1986. That was when they were given a mandate for what the interest rate could be used.

"You can compare that with a military division that had no weapons. They controlled the currency regulation, but could not set the key rate without the approval of the government. That is a very risky policy. Politicians will always keep the interest rate lower that it ought to be," says Klovland.

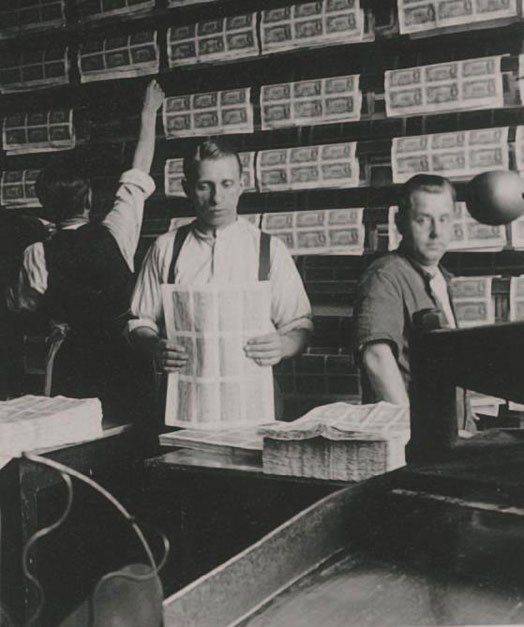

New technology made both regional networks and our own production of bank notes superfluous and inflationary. The last branches were closed down in the 1980s. Before that, the production of banknotes was located in the basement of the bank. At that time, the bank was very much like an industrial firm.

"If you were employed in Norges Bank in 1850, you were a banknote writer, a person who signed banknotes. If you skip 100 years forward in time you are a note printer, and today you would be an economist to put it bluntly," says Øksendal.

Facts

- "The Monetary History of Norway 1816-2016" will be published in connection with Norges Bank's 200th anniversary in 2016. This book looks at the development of the financial system and the central bank's role in a historical perspective.

- The book is in English and will be published by an international publisher. It has been written by and for economists.

- In addition, Norges Bank will publish a book about Norges Bank in Norwegian, written by historians under the direction of Professor Einar Lie at the University of Oslo. It will focus more on institutional conditions and political and economic issues.

- Jan Tore Klovland is a professor in the Department of Economics at the Norwegian School of Economics (NHH). He recently had a scientific article on the price history in Norway in the period 1777-1920 accepted in the publication, The European Review of Economic History, which is a spin-off of this project.

- Lars Fredrik Øksendal is currently employed as a researcher at Norges Bank. He has a doctor's degree from NHH and has many international publications in the field of historical monetary economics, especially from the period of the gold standard prior to the First World War.

This article was first published in NHH Bulletin nr. 3 2014, in Norwegian.

Read more about Jan Tore Klovland

Printing bills in 1939, the central bank of Norway.

Researcher Lars Fredrik Øksendal and Professor Jan Tore Klovland.

Foto: Helge Skodvin

|